Hills of Hassan district plagued by perennial human-animal conflict

Giant fences or elephant translocation might not be the right solutions to resolve the problem.

On November 1 last year, around 8 am, Manu H.G., a 34-year-old paddy and coffee farmer from Hebbanahalli village in Sakleshpur taluk of Hassan district set out to visit the Chamundeshwari temple, some 4 kilometres from his house. That was the last time his family, consisting of his wife and four-year-old son, his brother and mother, saw him. Manu used to visit the temple, which is in the middle of a coffee plantation, twice a week, taking a shortcut that led through a narrow trail flanked by a thick coffee plantation and an overgrown area of government land.

| Photo Credit: VIKHAR AHMED SAYEED

“When Manu didn’t return, we followed the path to the temple and discovered his trampled body around a kilometre from the house; an elephant had killed him,” said Madhu H.M., Manu’s brother, pointing to the mud path that began a few metres away from their tiled-roof cottage and trailed off into the dense undergrowth. As word of Manu’s death spread, hundreds of people from Hebbanahalli and the surrounding villages started gathering at the spot where he was trampled. Given that this was the sixth such death in the district in the last year alone, tempers ran high. Villagers and activists refused to remove Manu’s body until late into the night when Gopaliah K., the State Minister of Excise and the Hassan district-in-charge, visited the family and assured them that action would be taken to reduce the risk posed by elephants.

For someone sitting in Bengaluru or Delhi, far from Sakleshpur and closely following the flurry of events that took place after Manu’s death, it would seem that the government did all the right things: Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai offered his personal condolences to the family, the solatium was hiked to Rs.15 lakh from Rs.7.5 lakh in mid December, teams from Karnataka Forest Department (KFD) increased their vigil, and a special Elephant Task Force was constituted to mitigate instances of human-elephant conflict across four districts of the State. But for people who live in the region these are but hackneyed and knee-jerk measures. They have seen it all before, and as Madhu told Frontline in early January this year, there can be only one permanent solution: The elephants have to be translocated. According to the irate villagers who gathered around Madhu, humans and animals, especially something as large as an elephant, just cannot coexist.

WATCH

Giant fences or elephant translocation might not be the right solutions to resolve the problem.

| Video Credit:

Vikhar Ahmed Sayeed, Razal Pareed & Jinoy Jose P.

According to the Elephant Census of 2017, India has close to 30,000 Asian Elephants. Of this, 6,049, the highest in a single State, were in Karnataka, distributed in the forests spanning an L-shaped arc originating from the outskirts of Bengaluru and running all the way to the border district of Belagavi. Along this broad corridor that runs mostly along the Western Ghats, elephants are found in the districts of Chamarajanagar, Mysuru, Kodagu, Hassan, Chikkamagaluru, Shivamogga, and Uttara Kannada. Significantly, a detailed study done in 2015 showed that 60 per cent of the elephant’s habitat in Karnataka was outside notified Protected Areas, making it inevitable for pachyderms to come into contact with humans, leading to conflicts that manifest in two ways: destruction of agricultural crops, and injury and death to humans.

| Photo Credit: VINOD KRISHNAN

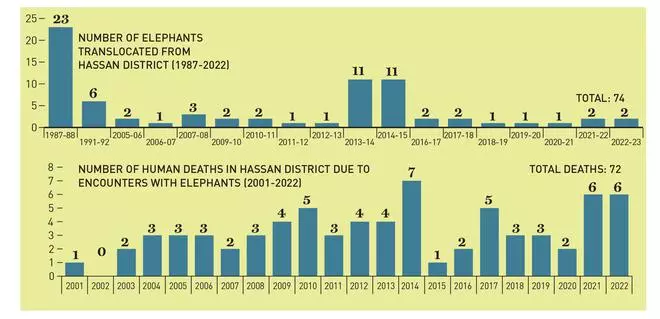

According to data from the KFD, 79 people have died as a result of elephant encounters in Karnataka between 2017 and 2021. The character and severity of the conflict varies across districts and is a major concern in the hilly parts of Hassan, where 72 people have died in the past 21 years. Over the past five years, 23 people in the district have been injured by elephants.

Along with loss of life, crop loss is a major concern across Sakleshpur and Alur taluks (Alur taluk is also in Hassan district). According to several large and small farmers in the region, it hampers production seriously. For instance, small farmers have reduced, or in some cases, completely stopped growing paddy, while large farmers, who lose swathes of crops to elephant foraging, have to stop labourers from working in a particular area for a few days after an elephant spotting. This means the labourer loses wages and the farmer loses revenue. The loss of productive coffee plants when an elephant ambles through a plantation is also a capital loss, as each plant is carefully nurtured and starts to yield only after five years.

The KFD has recorded 37,891 separate cases of crop loss in Hassan district caused by elephants since 2007, for which a total compensation of Rs.14.91 crore has been disbursed. Farmers complained that the compensation was “highly inadequate”, with one of them saying the sum “needs to be multiplied 100 times” to quantify the actual losses suffered due to crop loss. Several large farmers have begun to erect solar-powered fences in their plantations.

Source: Karnataka Forest Department

Another issue that has emerged is of children missing school days whenever elephants are seen in the neighbourhood. Dairy farming activities are also affected. Rohith B.S., the owner of Kithlemane Estate, who described himself as a “fifth-generation planter”, put it pithily, “I say this is my land, the elephants say it is their land. It is like a war.”

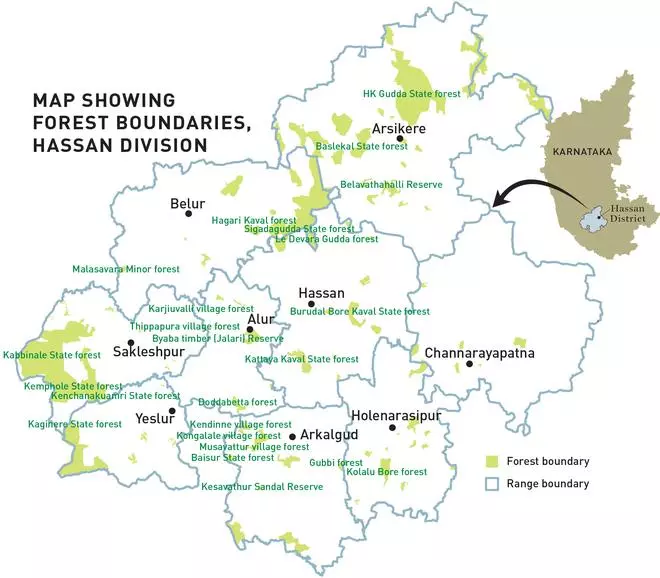

Looking at the forest map of Hassan district to get a sense of this “war” can be misleading because the designated forests areas are patchy and fragmented, giving the impression that there are hardly any forests in the district, and ergo there should be no elephants. This is not an incorrect observation, but a physical survey of the landscape from an elephant’s perspective would reveal that Sakleshpur, Alur, and Belur taluks have dense forests as the rolling hills here are solidly covered with coffee plantations and are contiguous to the adjoining protected areas. Tall trees are planted to provide shade for coffee bushes. Thus, the verdant plantations, depending on the season, provide a delightful smorgasbord for the elephants: jackfruit, coconut, areca, banana, and fresh grass. The valleys between the undulating hills are planted with paddy, which lures the jumbos during harvest season. And the elephants also eat bamboo.

| Photo Credit: VIKHAR AHMED SAYEED

The plantations across the area are also dotted with bountiful water tanks, another magnet for the elephants. Thus, as far as the elephant is concerned, this is an ideal habitat.

Translocating elephants

The KFD had previously suggested translocation of the elephants as a solution; that is, capture them physically and remove them from the area. Way back in 1987-88, about 23 elephants (12 captured from Kodagu) were removed from the region with this aim.

Then, between 2013 and 2015, after the release of the Karnataka Elephant Task Force (KETF) report, which designated the area as an “Elephant Removal Zone”, 22 more elephants were removed. The matter had reached the Karnataka High Court, which in its order delivered in 2013 stated: “All elephants in this region, currently estimated to number 25, be removed as soon as possible through capture, taking all due precautions and care to minimize trauma to animals during capture and subsequent training.”

Source: Karnataka Forest Department

Even after this massive effort, a handful of elephants remained in the area, which, according to Rohith, was “a violation of the High Court order”. One or two “difficult” elephants, usually males, have been captured annually since then, but the problem persists and the elephant population in the area has grown to 65 to 75 in the last decade.

So how does one “manage” this thorny conflict that appears to have no permanent solution?

Tracking and notifying

The Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) has developed an Early Warning System (EWS) that may provide an answer. Nisar Ahmed, the field coordinator of NCF’s field station in Kenchammana Hoskote in Alur taluk, explained how the EWS worked. Work starts at 5.30 am at the field station, with Ahmed and four field assistants setting out in different directions to follow up on elephants they have seen the previous evening. The elephants in the area are not part of a single large herd, but form several small herds. Some male elephants also roam the area on their own.

Ahmed and his team, which includes members of the Kadar tribe who are skilled trackers, have their work cut out as they simultaneously track up to 10-12 distinct groups or individuals at one time. Some of the matriarchs leading the three main elephant herds have been radio-collared, which makes it easier to follow their movements, but for the rest, the team depends on sight and the ability to recognise individual elephants. Once an elephant or a herd of elephants is spotted, the message is relayed back to Nandini Yuvaraj, the data operator at the field station, who collects this information and notes it down.

The GPS locations of the elephants are continuously shared over WhatsApp with members of the KFD and planters, who further share this information in their networks. The NCF also has a unique database of over 7,000 mobile telephone numbers with village-wise categorisation that covers 319 villages. Thus, if an elephant is sighted in a particular location, SMSes are sent in bulk to the numbers within a radius of 5 km. This information usually reaches people before 7.30 am just as they are getting ready for the day. For example, if a coffee planter receives information that an elephant or a herd on his estate, he ensures that the workers avoid that block of the plantation.

| Photo Credit: VIKHAR AHMED SAYEED

The same exercise is repeated in the evening. Through this simple way, Ahmed claims that the “surprise encounters” with elephants, which usually take place in the mornings or evenings, have reduced considerably. “Apart from the EWS, we have also installed display boards and alert lights in several villages to warn inhabitants of elephant movement,” said Ahmed.

Prabhu I.B., Assistant Conservator of Forests of Hassan Sub-Division, said that the KFD followed a similar routine in Hassan, where it has formed 26 Anti-Depredation Camps (ADC) and five Rapid Response Teams (RRT). The mandate of these teams is “to track the elephants, warn villagers in the area, and, if there are any issues, even drive the elephants away.”

Following Manu’s death, a separate Elephant Task Force, which basically does the same task as the ADCs and RRTs, but with additional personnel, was constituted. In theory, all these units of the KFD and the NCF are tracking elephants independently, but in the field, their work often overlaps as everyone is following the same set of elephants with the same goal: to use early warnings and thus reduce man-elephant confrontation. While these measures mitigate the conflict, can there be a permanent solution?

Fencing, a solution?

According to Prabhu, one idea could be to fence Hassan’s border with neighbouring Kodagu district along the Hemavathi reservoir, from where elephants enter Alur taluk. Considering that this fence has to withstand the brute strength of an elephant, railway barricades are being used for the purpose. “We have envisaged the construction of a 24-km barricade, of which 9.5 km has been completed and the remainder will be done this year. Once the barricade isup, the remaining elephants in Hassan can be translocated,” Prabhu said optimistically.

Ananda Kumar M., a senior scientist with NCF, who is familiar with the problem in Hassan, has worked on issues of elephant-human conflicts across the country and followed international developments as well. He is a vocal opponent of the move. “If translocation is seen as a tool for conflict resolution, it is a failure because we are only translocating the animal and not mitigating the problem. In Hassan, several elephants, usually males, have been captured over the years and each time an elephant has been captured, two-three from outside fill the gap,” said Kumar.

He also disagreed with the recommendations of the KETF report: “There is no logic in the categorisation of this region as an ‘Elephant Removal Zone’. By that measure, elephants must be removed from 60 per cent of their habitat in Karnataka. I also don’t think building railway fences is a solution; the elephant population in Hassan is not an isolated population but a contiguous one. Elephants are coming from and going to forests in Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary, Bisle Reserve Forest, apart from Kodagu. Barricading will increase the conflict tremendously.”

Is there a permanent solution to the problem? “With concentrated efforts,” Kumar responded, “we can minimise human deaths to zero, but managing the conflict is the only permanent solution.”

The Crux

- According to the Elephant Census of 2017, India has close to 30,000 Asian Elephants. Of this, 6,049, the highest in a single State, were in Karnataka.

- A detailed study done in 2015 showed that 60 per cent of the elephant’s habitat in Karnataka was outside notified Protected Areas, making it inevitable for pachyderms to come into contact with humans.

- According to data from the Karnataka Forest Department, 79 people have died as a result of elephant encounters in Karnataka between 2017 and 2021.

- The KFD has recorded 37,891 separate cases of crop loss in Hassan district caused by elephants since 2007, for which a total compensation of Rs.14.91 crore has been disbursed.

- The Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) has developed an Early Warning System (EWS) that may provide an answer.